-

Share on Facebook

-

Share on Twitter

-

Share on LinkedIn

-

Copy link

Copied to clipboard

GHO, Aave, and the future of stablecoins

Today saw the confirmation of one of the more interesting developments of the year in DeFi innovation with the Aave DAO vote on the GHO stablecoin. Proposed back in June 2022, GHO isn’t the most original concept in the world – an algorithmic stablecoin built on multi-collateral systems and mintable from the get-go against ETH, GHO on launch hence operates very similarly to DAI – or, at least, DAI in its original form, given that it is now overwhelmingly backed by USDC (i.e. a centralised stablecoin with the risks associated with that)

Executive Summary

-

The Aave protocol is currently voting on enabling the first batch of mints for its proposed stablecoin GHO.

-

GHO is an overcollateralised algorithmic stablecoin that allows users to keep their collateral yield-bearing within Aave.

-

The move opens some questions about the trajectory and future of centralised stablecoins.

Today saw the confirmation of one of the more interesting developments of the year in DeFi innovation with the Aave DAO vote on the GHO stablecoin. Proposed back in June 2022, GHO isn’t the most original concept in the world – an algorithmic stablecoin built on multi-collateral systems and mintable from the get-go against ETH, GHO on launch hence operates very similarly to DAI – or, at least, DAI in its original form, given that it is now overwhelmingly backed by USDC (i.e. a centralised stablecoin with the risks associated with that)

The edge GHO is supposed to have over similar products is that, apart from DAI’s shift over the last couple of years meaning that there largely isn’t a major stablecoin of the type in the place, users are still able to earn collateral on their assets being locked to create/borrow GHO through the Aave platform. This is an interesting twist, because it represents something of a different approach to what we’ve generally seen in attempts to build new stablecoins over the last few years (in terms of spectacular failures like UST and IRON, but also in terms of relative successes like FRAX); that is, Aave are embracing overcollateralisation here, rather than trying to chase undercollateralisation.

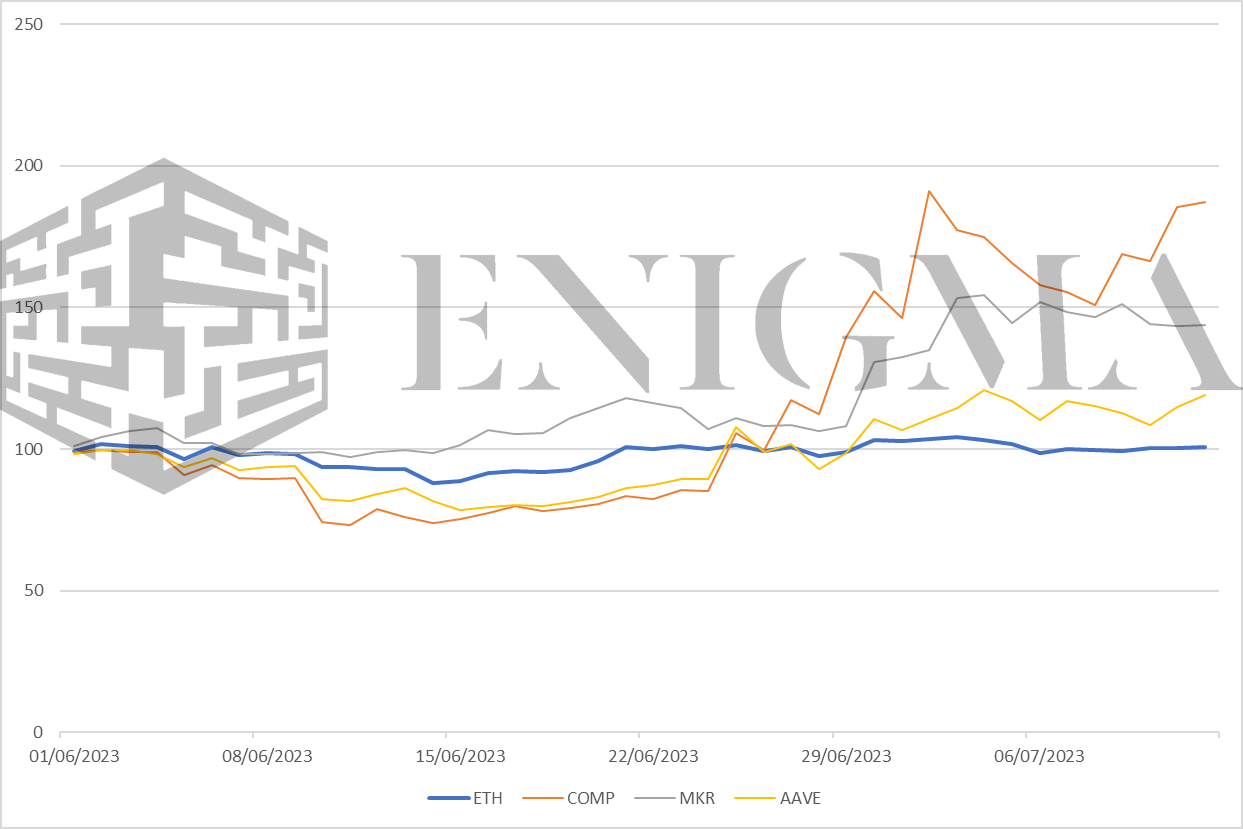

It remains to be seen how successful Aave’s big bet will be with GHO. Like most DeFi blue-chips, both Aave and its token AAVE have been in essentially a state of constant decline since the organic market top in May 2021; AAVE still boasts a market cap of over a billion but is down 88% from its all-time high, albeit having seen significant gains in the last few weeks along with several other blue-chips:

There are a number of reasons for this, but a large one is that the services offered by these blue-chips, particularly in terms of pure yield, look less and less exciting as real-world risk-free rates spike all over. At a current snapshot, Aave currently offers a deposit APR of 1.84% on ETH, between 2 and 3% on DAI/USDC/USDT, and its highest rate is just over 4% on CRV (which has also booked recent gains, but is looked upon as a severe risk due to a huge portion of the supply currently being held as collateral for a massive USDC loan on Aave itself – actually bringing as it stands a severe risk of liquidation and bad debt on Aave’s part as a result).

The big push for GHO is to take advantage of the fact that some sort of return can be obtained, and to turn it into a base layer stablecoin for DeFi. This, naturally, is ambitious to put it mildly; but the timing does make some sense, as stablecoins – particularly in permissionless markets – find themselves at an odd moment.

USDC has been the de-jure stablecoin for permissionless markets since DeFi Summer in 2020. Why? Mostly, this is a case of right place and right time. DAI was at the time seen as small and too unstable (the price mechanisms in the place at the time, coupled with the relatively small market cap of around $100 million, meant that DAI would regularly go off-peg by 1-2%, albeit to the upside), while USDT was still held in relatively low esteem after its 2018 ‘bank run’ (even though it had weathered it fine), and in any case was focusing on multi-chain provision at the time to meet simpler real-world uses (this was the era where, by some accounts, USDT market cap on Tron may have eclipsed its status on Ethereum at some points).

While USDC went from strength to strength for the most part over the next couple of years, the last few months have not been the kindest to it. The collapses of Silicon Valley Bank among others in the US caused a brief suspension of redemptions and a depeg over the weekend of 12th March to $0.89 at one point; this is relevant because, even though the consequences overall were relatively limited (i.e. nothing broke in the DeFi world on the basis of it), it broke through an aura of total invincibility that USDC until that point had enjoyed. The SEC investigations into Coinbase also did not help; USDC parent Circle has enjoyed extremely close relations with Coinbase (and had gone all-in on staying onshore in the US), with USDC itself being created in partnership with Coinbase explicitly as an USDT-alternative in 2018.

USDC remains held in high esteem overall, of course; however, it has seen a massive decline in its market cap and effective AUM over the last 12 months, going from a peak of around $56 billion to just $27 billion and falling (per CoinGecko data). For Circle’s part, it feels like the company is trying to find a slightly different niche, going back to focusing on its relationships with centralised entities rather than decentralised ones. Significantly, it launched an Euro stablecoin (EUROC) last July; while most stablecoin issuers have experimented with non-USD stablecoins at one time or another, and e.g. Tether did re-issue an Euro stablecoin a couple of years ago (having initially launched and shuttered one in 2014 and some time in 2018 respectively), the experience has always been that it is nearly impossible to drum up enough of a network effect to make them useful without seriously strong central rails. This seems to be the direction in which Circle are heading – not going fully permissioned, but not going out of its way to be the de jure currency of non-permissioned markets, either.

Tether, for their part, are happy to embrace that, and USDT market cap (after a steep decline between May and July of last year) is at all-time highs today at $83 billion). USDT has gained an ubiquity as a currency of pure value storage and transfer that it never previously possessed, either in the 2017 bull market (where almost everything was still BTC-denominated and Tether sat at a sub-$500 market cap as late as November), the 2020-1 run-up, or any points in-between, with the possible exception of that period around 2019 where smart contract applications still remained largely theoretical and stablecoin value transfer purely revolved around real-world deals and Ponzi schemes like PlusToken and Forsage.

However, to some degree, Tether now finds itself as a victim of its own success, particularly with regards to its business model. Why? The financial models for stablecoins, putting asides any conspiracy theories about market manipulation and the like, has always been simple; the stablecoin provider redeems and issues at part, and acts as a pseudo-bank in the interim, investing reserves predominantly into short-term money market operations. In Tether’s cases, there were always rumours over how wise some of these investments were; constant rumours abounded about Chinese commercial paper, and we know of cases like the company loaning $1 billion to Celsius (albeit that being heavily overcollateralised with BTC and other crypto stablecoins and not incurring any serious problems for Tether in the end).

This was largely overlooked in a low-rates environment – the utility of the service that USDT provided vastly outweighed any concerns about whatever they were collecting with treasuries at 0.50% – but is started to be looked at far more critically now. We have a curious case where perception on Tether has shifted from “they must be doing something wrong to be profitable” to “they can be profitable while doing everything right, and that’s unfair”. T-bills are now trading at the same 4-5% rate that appeared to require some back-office financial engineering magic to the untrained eye, and that companies like Circle were able to pass on, just a year ago.

Despite this, Tether market cap has largely kept rising, and attempts to go head-to-head with it have generally been disasters. FTX were looking to create a new stablecoin just before their collapse, having always had an odd relationship with USDT and with how it was used on their platform (Alameda were heavily involved in Tether creations and redemptions, but Tether was also categorised differently to other stablecoins on the FTX platform). Binance launched BUSD in conjunction with Paxos in 2019, and were pushing BUSD trading pairs over USDT heavily at around the same time; New York state regulators ordered a phased shutdown of the token in February. Recently, Binance have started to push TUSD as an alternative instead, but that has faced its own litany of concerns and criticism, culminating (so far) with a severe flash depeg to as low as $0.80 a couple of weeks ago due to concerns over possible exposure to Prime Trust.

Tether is an extremely strong incumbent, and it’s hard to see a stablecoin going into its arena and coming out on top as it stands. However, there are spaces in which it will never fully be trusted, never be fully utilised, just because of past reputation and past operations. The GHO launch (if the proposal – which has received quorum already – does pass the DAO, minting is expected to open on Saturday 15th) is one to keep an eye on, not only for its own sake but for what it might mean for the older DeFi protocols’ attempts to essentially revive themselves coming into the next bull market.